by MISA Regional Director Dr Tabani Moyo

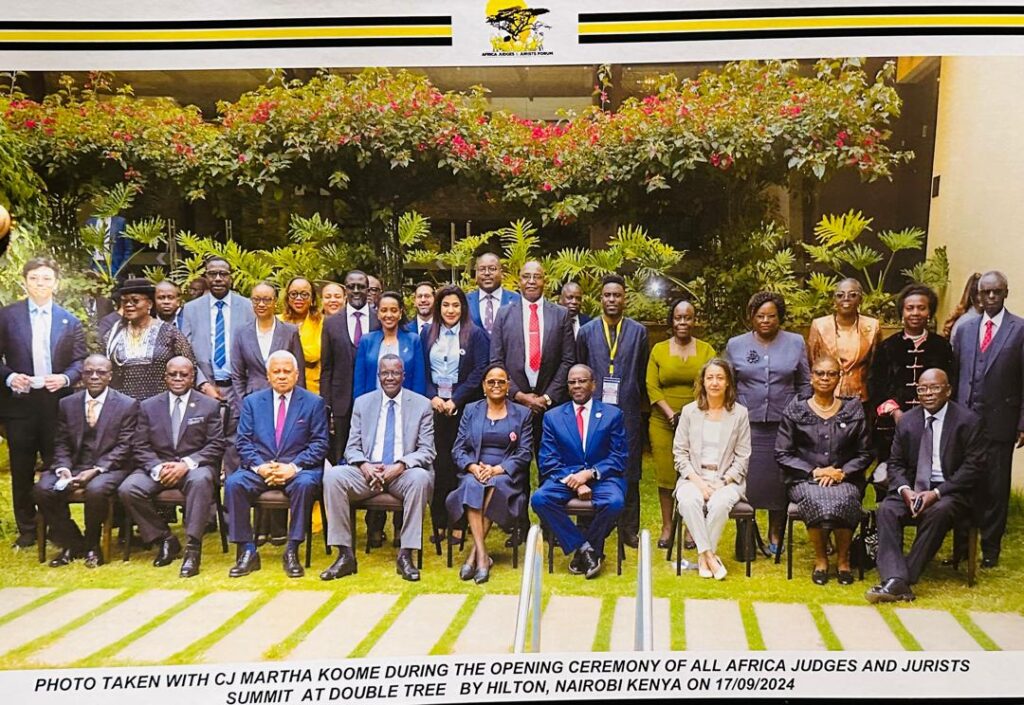

My Lords, My Ladies, the leadership of the Africa Judges and Jurists Forum (AJJF), distinguished delegates to the All Africa Judges and Jurists Summit, it is a great honour for MISA to engage in this august meeting on the nexus and intricate intersectionality between technology and access to justice in Africa.

Chairperson and distinguished guests, we have never been so well placed as we are today to take decisive forward steps towards creating a people-centred society, especially one that places the generally marginalised at the centre of accessing and utilising judicial services through technology.

As we enter the last decade of the Sustainable Development Goals and eclipse the first decade of the African Union Agenda 2063, the continent and the region must leave no one behind, especially the historically marginalised groups.

This can be achieved by ensuring that there are enabling conditions for them, like everyone else, to utilise judicial services online and that the means (technology) and the end (justice), should remain within everyone’s arms reach irrespective of social, economic or political standing.

Dr Tabani Moyo MISA Regional Director addressing delegates at the All Africa Judges and Jurists Summit, Nairobi, Kenya

I congratulate the AJJF on the successful convening of this timely forum as a testament to your admirable efforts in addressing societal challenges, especially in the age of technological changes, bearing in mind that less than 50% of the people of Africa are online.

It is worth noting that legal systems are crucial in determining how society advances, from the creation of governments, constitutional enactment of democratic ideals, defending human rights and to controlling business transactions.

The African Union’s (AU) Agenda 2063 has brought the issue of justice back into the spotlight, especially regarding the third objective, which describes an “Africa of Good Governance, Democracy, Respect for Human Rights, Justice, and the Rule of Law.”

This goal emphasises how gender equality, improved socio-economic opportunities, access to justice, and personal financial security are all critical for equitable and sustainable development and progress.

Every society must have a criminal justice system in place to protect justice, preserve law and order, and safeguard the safety and welfare of its people. But conventional methods of handling the criminal justice system have frequently run into several problems, including inefficiency, hold-ups, and a lack of funding.

The swift progress in technology in recent times has offered novel prospects to tackle these issues and transform the functioning of the criminal justice system.

The Pandemic, A Catalyst for Digital Courts

Following the Covid-19 pandemic, some innovative court systems that had been experimenting with technology before the pandemic saw an opportunity to solve a problem and modernise their courtrooms as courtrooms around the world closed and backlogs in cases grew even faster.

Along the way, they have learned a great deal about how to use technology to improve the fairness of the legal system in the post-pandemic environment. In that regard they have made great strides towards achieving access to justice.

But what started out as a lifesaver to keep the lights on in an emergency soon began to prove its worth. As judges, attorneys, and litigants began to communicate more effectively during the pandemic and beyond, court systems that used digital solutions were able to clear the backlog of cases.

On a broader scale, “access to justice” signifies the process through which individuals of diverse backgrounds can access the legal process. Nonetheless, millions of people do not have critical access to justice, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).

The justice gap persists due to the inaccessibility of relevant technologies, chronic poverty and marginalisation, disproportionately affecting the most vulnerable who struggle to uphold rights such as the right to education and access to clean water and aid against gender-based violence, thereby exacerbating their impoverishment.

Pervasive obstacles include prolonged court cases, high costs, corruption, intricate legal processes, inadequate legal representation, and concerns about judicial equity, which hinder access to justice.

The High-Level Panel on Emerging Technologies (APET) of the African Union believes that integrating and utilising emerging technologies, such as blockchain, machine learning, and artificial intelligence (AI), can positively impact the administration of justice throughout the continent.

These cutting-edge technologies are changing how the law is administered and practised, providing increased effectiveness, openness, and inclusivity opportunities. African governments should invest in developing technologies while putting strong privacy safeguards in place to protect the private information of case participants, according to APET, to accomplish this goal.

Improving the internet and technology infrastructure and ensuring these resources are more accessible to marginalised groups is essential. This can be done by lowering internet costs for underprivileged areas. This approach optimally harnesses emerging technologies, bridges the potential digital divide and advances equitable access to justice. Moreover, comprehensive training for court personnel in operating digital equipment is imperative.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are becoming increasingly important in the legal field. These tools are invaluable for legal research because they can quickly analyse large amounts of data to find trends and forecast outcomes.

AI-driven document evaluations speed up the litigation’s discovery phase by quickly locating relevant papers and pointing out problematic areas. By shortening the time needed for manual reviews and minimising human mistakes, these developments improve accuracy. Legal Robots and Paralegal AI are two examples of well-known AI legal tools.

APET also advocates for the adoption of blockchain technology by AU Member States in addition to AI tools to improve security and transparency in legal systems, ultimately promoting trust. Blockchain technology can potentially revolutionise the handling of legal contracts and documents by offering a transparent and safe digital framework for data exchange and preservation.

Blockchain technology makes it possible to safely store and confirm important documents like wills and property deeds, creating an immutable record that is readily accessible and verifiable. This invention may make it easier to determine who owns a document and settle legal disputes around it.

In addition, using virtual reality and online platforms for dispute resolution can improve the effectiveness of legal representation and advance fair judicial systems throughout the continent.

Applications for virtual reality can replicate courtroom settings, allowing judges and jurists to practise their skills in real-world settings through simulated trials. These applications lessen the need for traditional litigation for dispute resolution by utilising algorithms and automated decision-making processes to support conflict resolution.

Sabine Katharina Witting, an Assistant Professor of Law and Digital Technologies, highlighted the following case examples in the Leiden University online blog:

- Kenya: how to convict a travelling sex offender

Simon Harris, a UK national, has been sentenced to 17 years and 4 months in prison by the Birmingham Crown Court for sexually abusing young Kenyan street children. The case is one of the first of its kind, because the victims did not testify in person, but gave testimony via international video link from Kenya.

This made life easier for the UK criminal justice system, as there was no need for the intensive planning of transport of the victims, parents and interpreters to the UK. The international video link also ensured that the victims, some as young as nine years, could give testimony in a familiar and safe environment, and without having to face Harris in court. As a positive side-effect, it hampered a typical strategy often applied by defence lawyers in similar cases, whereby it is claimed that the victims have been lured into giving a false testimony because of the incentive of travelling abroad.

Therefore, the Simon Harris case presents itself as a remarkable milestone of leveraging technology to bring travelling child sex offenders to justice.

Kenya Chief Justice Martha Koome welcoming delegates as the host

- South Africa: creating a safe space for victims in court

A simple, yet very effective use of technology in the criminal justice sector is the use of CCTVs in courtrooms. The mere visual confrontation with the perpetrator can be so disturbing for the victim, that it might interfere with their capability to testify, and leave them with an additional traumatic experience, simply due to the victim-hostile court environment. To mitigate these effects, the victim can be given the opportunity to give evidence from a remote witness room, while being linked to the actual court room via CCTV or video link.

The use of CCTV or video link in the courtroom requires special provisions in national criminal procedures acts. While the fair trial principle normally requires the victim to give evidence in the presence of the accused to give him or her the opportunity to cross-examine the witness, it has been acknowledged that this right cannot be granted without limitation, when dealing with vulnerable witnesses such as children. Their right to dignity and physical and emotional well-being justifies the interference with the accused’s rights to direct interaction with the victim, and hence allow the victim to give evidence via CCTV or video link.

South Africa acknowledged the benefits of such a provision for vulnerable witnesses in 1996 and introduced a corresponding provision in its Criminal Procedures Act. Section 158 now allows a witness to testify via CCTV or similar electronic media, either based on the court’s initiative or the prosecutor’s application.

- Namibia: replacing the examination in chief with a video recording

Multiple victim interviews are common in the criminal justice system for a variety of reasons. Firstly, the victim might take more time to build rapport with the interviewer, and hence not give a full disclosure in the first interview. However, the victim is often exposed to multiple interviews against his or her will.

The reason for this is that various stakeholders, such as police officers, social workers, medical doctors and prosecutors come in at different stages of the criminal justice process and might require slightly different information. So even if the child fully discloses the incident in the first interview, she might have to repeat the story several times for different stakeholders.

This process is problematic for several reasons: it increases the risk of re-traumatisation, the risk of the child recanting the initial statement, creating contradictions within the statement, or it can simply lead to the child’s unwillingness to further participate in the process.

By introducing a video recording of the initial interview, all these risks can be tremendously mitigated: instead of forcing the child to tell the story again, the initially recorded statement can be displayed. This can even go as far as replacing the examination-in-chief with the video recording.

Similar to the use of CCTVs in court rooms, this requires a specific provision in the Criminal Procedures Act, as it takes away the accused’s opportunity of cross-examining the victim. The Namibian Criminal Procedures Act states that evidence of a child below the age of 14 years can be given in the form of playing a video record of the making of the statement if the person to whom the statement concerned has been made, gives evidence in such criminal proceedings.

Therefore, the defence has at least the chance to cross-examine the interviewer but does not interact directly with the child. This approach is obviously only efficient if the recorded interview is conducted in a technically sound manner (e.g. no leading questions) and if the child’s statement does not leave questions open that the interviewer cannot sufficiently answer during cross-examination. Otherwise, the court might accord less weight to the child’s statement, and a conviction might depend on corroborative evidence.

Conclusion

Lastly, if technology is used to speed up the criminal justice system, its efficiency, equity, and public safety will significantly improve. Throughout this thorough analysis, we have examined how technology can be applied to improve the criminal justice system, including court procedures, corrections, and law enforcement.

Some of the attendees of the All Africa Judges and Jurists Summit

One of the main advantages of utilising technology is that it can decrease manual, time-consuming chores and streamline operations. Data analysis, record-keeping, and case management are examples of administrative tasks that can be made easier by automation and digitisation.

By doing away with needless paperwork and manual data entry, criminal justice professionals will concentrate more on important duties that call for their skills.

Technology has a lot of potential in law enforcement. Modern surveillance systems, biometric identification, facial recognition, and predictive analytics are examples of how technology may improve law enforcement skills and help with early discovery, quick reaction, and crime prevention.

Technology can also greatly expedite investigative processes by offering data management, analysis, and evidence-gathering tools. Law enforcement organisations can benefit from the speed, accuracy, and informed decision-making of digital forensics, data mining, and AI-powered algorithms.

Legal technology also offers transparency and easy access to legal information. Lawyers can quickly and easily access a wide range of legal resources and case law through online platforms, such as legal databases, virtual libraries, and government transparency portals.

However, while technology offers numerous benefits, it is crucial to acknowledge and address potential challenges and risks. Privacy concerns, data security, algorithmic biases, and accessibility issues must be carefully addressed to ensure technology’s ethical and responsible use in the criminal justice system.

Adopting and implementing cutting-edge technical solutions may also be financially challenging, necessitating careful planning and budget allocation.

Technological innovations can accelerate the criminal justice system and improve efficiency, access to justice, and outcomes for all parties involved if they are welcomed and thoughtfully implemented.

To create a more fair and efficient criminal justice system going forward, legislators, attorneys, and technologists must work together to take advantage of these opportunities and overcome these obstacles.

Above all, technological advancement cannot be discussed in isolation from the enabling conditions such as infrastructure development and the supporting conditions which make the Internet accessible, affordable and available at all times.

Thank You

In a historic development, the AJJF brought judges and jurists from all continental regions to Nairobi, Kenya, from September 17th to 19th, 2014, as a holistic approach to strengthening the judiciary in an ever-evolving environment.